Smishing vs. Phishing: Understanding the Differences

source: proofpoint.com | image: pexels.com

What have smishing offenders learned from their phishing email counterparts?

Email-based credential theft remains by far the most common threat we encounter in our data. But SMS-based phishing (commonly known as smishing and including SMS, MMS, RCS, and other mobile messaging types) is a fast-growing counterpart to email phishing. In December 2021, we published an article exploring the ubiquity of email-based phish kits. These toolkits make it straightforward for anyone to set up a phishing operation with little more than a laptop and a credit card. Since then, we’ve tracked their evolution as they gain new functions, including the ability to bypass multifactor authentication.

In this blog post we’re going to look at smishing vs. phishing and what smishing offenders have learned from their email counterparts, as well as some significant differences that remain between the two threats.

Setting the (crime) scene

A modern email phishing setup can be as simple as one person with a computer and access to common cloud-hosted services. But for a smishing operation, the picture is somewhat different. While software smishing kits are available to buy on the dark web, accessing and abusing mobile networks requires a little more investment.

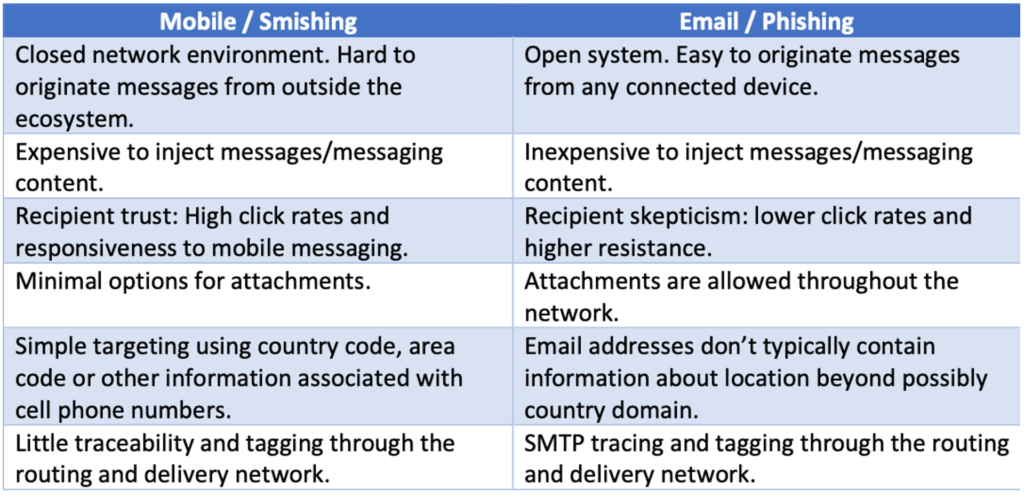

Unlike the internet, mobile networks are closed systems. This makes it more difficult for people to anonymously create and send messages across the network. To send a malicious mobile message, a smishing threat actor needs to first gain access to the network, which requires sophisticated exploits or dedicated hardware. “SIM bank” hardware has come down in price recently, but units can still cost hundreds or even thousands of dollars, depending on how many SIM cards are supported and the number of simultaneous mobile connections they can handle. And of course, the criminals also need to pay for active SIM cards to use in their SIM bank. As mobile network operators identify and exclude malicious numbers, new SIM cards are needed, creating ongoing connection costs.

The physical nature of mobile networks also increases the risk of detection for smishing threat actors. In the UK case noted above, the culprit was arrested in a hotel room. This is not uncommon—network operators can use cell towers to pinpoint where malicious activity is coming from. Smishing offenders therefore need to be highly mobile, moving frequently to avoid getting caught.

Social Engineering and Other Similarities

While there are important structural differences between smishing vs. phishing, when it comes tosocial engineering these attacks have plenty in common.

Fundamentally, both approaches rely on lures that prey on human psychology. They use tendencies such as loss aversion and biases towards urgency and authority to convince victims to perform an action. Differences between email and mobile messaging formats mean that smishing attempts are shorter and less elaborate than many email lures. But while the execution may vary, the impetus of a missed package or a request from the boss remains the same.

Smishing and traditional phishing also share similarities in how they target potential victims. In addition to high-volume messaging, both also make use of more specific “spear phishing/smishing” techniques. In these attacks, cyber criminals use detailed research to tailor messages, often targeting higher value people within an organization. As we’ve explored on this blog before, mobile phone numbers can be easily linked to a range of personal information, making them a potent source for spear smishing expeditions. As with their targeting behavior, we also see similar seasonal campaign patterns with both phishing and smishing. Summers are usually slower and activity is often suspended completely during winter holiday periods.

For many email users, ignoring spam and other basic kinds of malicious message delivery has become second nature. But since mobile messaging is newer, many people still have a high level of trust in the security of mobile communications. So, one of the most important differences between smishing vs. phishing is in our basic susceptibility to attack. Click rates on URLs in mobile messaging are as much as eight times higher than those for email, vastly increasing the odds that a malicious link will be accessed when sent via SMS or other mobile messaging. This responsiveness remains even in markets where services like WhatsApp and Messenger have replaced SMS as the dominant means of mobile text communication. We expect organizations and businesses to send us important messages via SMS and act on them quickly when they arrive.

The prevalence of links over attachments is another important differentiator. Mobile messages are not an effective way to send malicious attachments because many devices limit side-loading and messaging services limit the size of attachments. Instead, most mobile attacks make use of embedded links, even when distributing malware such as FluBot which spread across the U.K. and Europe last year. Email attacks, on the other hand, still see around 20-30% of malicious messages that contain malware attachments.

Personal phone numbers also expose location information in the form of an area code. This can provide other opportunities for location- and language-based tailoring that aren’t present in an email address. Similarly, end users have limited ability to see how the SMS message was routed, seeing only the number it appears to have been sent from. While both mobile numbers and email addresses can be masked, email headers contain much more detailed information about how a message was routed to the recipient and may allow them to spot a malicious message.

Conclusion

As a common point of connection between our personal and professional lives, mobile phones are a high-value target for cyber criminals. A single device may contain accounts giving access to individual and corporate finances, sensitive personal information and confidential commercial documents. In the U.S. last year, smishing rates almost doubled, and that trend is set to continue this year. And while smishing operations have to work with character limits, location constraints and increased overheads, it’s clear that lessons learned from email phishing are helping to maximize their returns. In fact, we believe that the success rate for smishing attacks is likely to be substantially higher overall than for email phishing, though the volume of email attacks remains many times greater.